The power of play: A key to reimagining early education for our time

Commentary: Vol 6, No 2 - October 2019

Dr Elena Chloe enters the room briskly as if she is on a serious mission to save the planet from invaders who are throwing trash over the school playground. Donned in a red vest with a blue letter E on the back, our superhero is in true form. She peers out of the window carefully examining the birds and deer and anyone who might intrude on the currently well-cropped space. Then, out of the corner of her eye, she sees a ruffle in the bush as the littering culprit heads for the swings. Zap she reaches her hand forward with an outstretched finger and sends positive vibrations that immediately levels the troublemaker who bolts from the set. The schoolchildren are safe again. Dr Elena Chloe has earned her title as “Dr” because she helped people.

Introduction

To the untrained eye, this fantasy scene is just that, an exercise in frivolity – imagination and fun. And though it is true that imagination and fun are at work, this play is serious business that harbours the seeds for academic and social learning. How? Let’s take another look. When she dresses the part of our untamed superhero, she is role-playing and examining the world from another perspective. This is an important social skill that will later feed into her theory of mind about how others think. It is precisely this kind of play that allows a child to understand that even though she detests broccoli, you might actually like the green vegetable.

Or take the well-established story line. The narrative begins in a setting – the schoolyard, with a conflict – someone is trashing the playground, and it brings us to a solution – zapping and hence a happy ending. We are all safe again. In these short, but coherent story lines, lies the foundation for reading. And all along, her language skills add to the drama and to the heroism. To her, the accolade of “Dr” is just about doing good for others.

If we can learn to look beneath the surface, we see the richness in play and can learn to harness its power as a strong pedagogical tool for young children. In our book, Becoming Brilliant, Dr Roberta Golinkoff and I argue that play embraces precisely the characteristics that allow us to move deftly from cradle to workplace. The so called 21st century skills. Doing an overview of the skills most often mentioned by chief executive officers that are imperative in a digital and global world, we scanned the literature to see which might be supported by the science of learning. Six C’s emerged:

- Collaboration: Learning how to get along, form communities, socially regulate impulses

- Communication: Grooming speaking and writing as well as listening skills

- Content: The familiar 3Rs but adding learning-to-learn skills like attention

- Critical thinking: Learning to marshal evidence in favor of a position

- Creativity: Innovation, entrepreneurial sense, using familiar parts in novel ways

- Confidence: Perseverance and growth mind set.

Each of this suite of skills has a rich scientific base, is malleable (such that teachers and parents can help children grow in each area, and is testable, though some assessments are better than others). In what settings do we have a real opportunity to develop these skills? In playful learning – in the sandbox – in preschool classrooms that are designed to promote play!

But alas, we must be careful in our design because not all play is created equal.

Play is a term that has been notoriously hard to define. It has been a subject of empirical study for many year waxing and waning in interest over many decades. In a very recent paper, Dr Jenn Zosh lead our team in a comprehensive definition of play suggesting that play occurs when the child is active (not passive); when the child is engaged and focused (rather than distracted); when the play is meaningful (rather than disjointed); when it is socially interactive; iterative (each time you come back to the play you can build on it or do something different); and when it is joyful. While some of these features are not absolutely necessary each time a child plays – you can play alone with construction toys – the very best advantages seem to come from play that shares all of the characteristics.

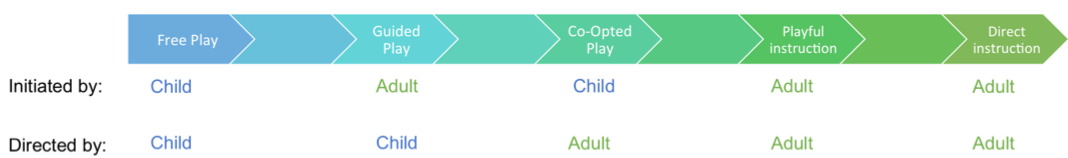

There are also different types of play. Traditionally, these have been coded as object play, rough and tumble or physical play, fantasy or dramatic play, and games. In our own work, we also talk about a continuum of play, an idea first discussed by Professor Doris Bergen in the 1970s. Our version is copied below. As you will see, when a child initiates and directs the play, it is called free play (building a fort out of the pillows on the sofa). When the adult initiates and the child directs, we call it guided play (a children’s museum or Montessori school in which the elements of the environment have been carefully prepared but the child uses her own initiative to move around the elements). These two forms of play can be contrasted with direct instruction in which the adult both initiates and directs the play. A number of studies from our laboratories show that if you have a learning goal – be it learning vocabulary for later reading or Science, Technology, Engineering and Mathematics (STEM) skills in baby geometry like learning shapes – guided play is better than free play for achieving those ends. In many cases, it is also better than direct instruction as children can generalise what they learn to new settings!

Internationally, though not as prevalent in New Zealand, preschools started to adopt a more direct instruction pedagogical approach to early learning. Indeed, play became a pariah as those in early education recognised the need to help all children – especially those from underserved areas, get the kind of rich exposure to print, number and STEM that they needed to be ready for success in school. In many parts of the world – the United States and England, for example, this meant taking formal school curricula and pushing it down into preschool environments, often draining the classroom of any play at all.

Does it not have to be this way? We can and have envisioned 6C classrooms that use a thematic play approach to achieve learning goals in a joyful way. Take the West Chester schools in Philadelphia, Pennslyvannia on the east coast of the United States. Two years ago, the school decided to move to full day kindergarten, which is the grade just before the start of formal school in the United States. The teachers for a particular grade met and decided on playful themes that would allow children to develop in each of the 6Cs. One group of teachers chose weather as the theme. When I entered the classroom, I saw 25, five-year-olds busy at work at various stations throughout the room. At one station a child holding a cardboard box peered through a tiny hole to ‘film’ the evening weather report while another pointed to a map of the country explaining the forecast, likely precipitation and the cold front that was headed our way. Wait, forecast, precipitation and cold front are complex vocabulary items that tap into complex weather dynamics that the children seemed to understand! At another station, children tried to solve a key mathematical problem. How many drops of rain will it take to fill a particular circle of a particular diameter? Carefully measuring each drop from a small device, the children even graphed their discoveries. Notice how this theme allowed children to flex their mental and social muscles for each of the 6Cs.

In a second room, I witnessed children digging into the world of fairy tale books. Faces were painted atop wooden spoons to create The Three Pigs, Goldilocks and the Three Bears, and Cinderella. I became the audience for a presentation of the Three Pigs and Goldilocks and when I asked which of the stories the child was doing she told me “both. She was doing a mashup!”

The school tells us that this play-based intervention helped them raise outcome scores and to do so less expensively than in their previously half day program. Further the children were so happy that it contagiously reached their parents and more and more children have been signing up for the program. Now, this is hardly a scientific experiment, because the full day kindergarten was introduced at precisely the same time as the play intervention. But, it is a proof of concept.

Bottom line? We can offer a very strong curricular focus for young children that is delivered in a playful learning pedagogy. And such programs are not just optimal for older preschoolers. Creating box structures that two year olds can crawl through, fantasy environments that two and three year olds can live in, all become possibilities in guided play. Add some free play as well, and children have a well-rounded experience that is also mentally and socially rewarding and that totally embraces growth in the 6Cs.

Perhaps it is time to reimagine early education through the lens of playful learning. Dr Elena Chloe and other little folks can often see a world that we do not. If we open our eyes to the possibilities, however, early childhood education can foster the power of play.

Reference

- Golinkoff, R.M., & Hirsh-Pasek, K. (2016). Becoming brilliant: What science tells us about raising successful children. Washinton DC: American Psycological Association.

How to cite this article

Hirsh-Pasek, K., and Golinkoff, R.M. (2019). The power of play: A key to reimagining early education for our time. He Kupu, 6 (2), 36-38.