Exploring children’s perceptions and working theories: Becoming a co-puppeteer, co-inquirer and conversationalist

Special Edition: Vol 6, No 3 - May 2020

This article is based on research carried out for my master's thesis (Winslow, 2019), which explored three- to five- year-old children’s perceptions and working theories of kindness. Literacy, in the traditional sense, was not an intended focus of this research, however, the importance of children’s ability to express the complexity of their perceptions and working theories became a central consideration for the research. What was needed was an approach to research that allowed children to express themselves within the parameters of their vocabulary, but still allowed the researcher to capture the fullness of their thinking and ideas on the rather complex topic of kindness. A case study methodology allowed the researcher to select multiple avenues of data collection. The two most important methods of data gathering were the observation and audio recording of the children’s puppet play and the conversations between the researcher and children about their puppet play. The outcome of these data gathering methods were rich and revealed dialogic conversations. The conversations became opportunities for children to discuss, share and expand on their working theories of kindness. Over the course of the research, the children became increasingly confident as puppeteers, storytellers and conversationalists. The researcher found herself as co-puppeteer and co-inquirer, rediscovering the importance of time and space for authentic conversations with children. Puppet play and conversations encouraged children and researcher to explore their perceptions and working theories together by revisiting and retelling favourite stories and characters, challenging existing ideas and building complexity over time and with practice. Puppet play also served as a mediating tool for the researcher to better understand children’s points of view on abstract concepts.

Introduction

Puppets have been used with children in the early years as they are able to take on any role and say things that kaiako (teacher) would not normally say. They can express uncertainty, confusion, pose problems, ask questions, and offer alternative ideas (Belohlawek, Keogh & Naylor, 2010). Puppets have been used extensively in research with children as a communication tool allowing children to develop their own characters complete with emotion, expression, thoughts, feelings and intentions (Alchrona, 2012; Bernier & O’Hare, 2005; Brēdikytē, 2000; Brown, 2005; Hunt & Renfro, 1982). Children are able to assign human qualities and emotions to puppets, thereby enabling them to express and explore associations, thoughts, feelings and intentions both during the interaction and as recollections. In a time where social and emotional literacy are so important, puppet play can provide a safe space for children to explore and make meaning of the complexities of social norms, social skills and different ways of being in a group.

Interestingly, puppets and puppet play appear to be less popular in early childhood settings than in previous decades. With a move away from structured, kaiako-led mat times, there may have been an unintended loss of time and space devoted to storytelling in this form of play. However, by taking an approach where the kaiako is a co-puppeteer, there could be a necessary resurgence in the use of puppets as a storytelling, teaching and learning medium.

Value of storytelling play and conversations in early childhood education

Narrative types of play, allow children to organise and make meaning from their recollections, experiences and fantasies (Belohlawek et al., 2010; Bruner, 1986; 2002). In this way, puppet play gives children a vehicle for telling, retelling and reframing their stories that is not reliant on the limitations of language, social skills or any of the constraints of their reality. This allows the kaiako to be a co-puppeteer, and effectively engage children in discussions about complex cultural constructs, such as kindness. Anggārd (2006, as cited in Alchrona, 2012) found that communication in the form of pictures or symbols, mediated children’s way of thinking, remembering, interpreting and fantasising. Research shows that children use more dialogue, reasoning, explanations and justification for their ideas where puppets are used in the classroom (Belohlawek et al., 2010). In addition to kaiako and children engaging in puppet play together, conversations, which support children to reflect on and revisit this play, can provide valuable insights into children’s perceptions and working theories (Winslow, 2019).

Conversations may seem like a ‘taken for granted’ method that kaiako engage in with children in early childhood settings. Authentic conversation however, requires time, space and a pace that is becoming less achievable in our increasingly busy learning environments. Voice, from a dialogic viewpoint, creates links between language and social contexts (Maybin, 2013) and children often choose to reproduce the voices of others to incorporate into their own voice, such as mimicking a kaiako or adding voices to a character. This shows us that children’s voice and articulation of thinking is influenced by sociocultural factors (Maybin, 2013). This includes influences from past experiences and the surrounding environment. Therefore, early childhood settings need to be intentional in creating spaces where dialogue and conversations can occur (Moss, 2007; Winslow, 2019) with kaiako who are curious about children’s perspectives (Hawkes, 2015; Winslow, 2019). This requires not only time, but also a sense of vulnerability on the part of the kaiako to listen intently, reflect deeply and have authentic conversations. Welcoming uncertainty and opportunities for exploration can be achieved through authentic conversations with children (Hawkes, 2015). This allows exploration of abstract social concepts, such as kindness or social justice, while reading stories, discussing books and telling stories about their own lives (Mackey & de Vocht-van Alphen, 2016). Puppet play, paired with authentic conversations provides a medium for children to explore, share, challenge and articulate their perceptions and working theories.

Methodology

A social constructivist epistemology underpinned this research, aligning beliefs about the social nature of learning with the play-based and relational pedagogy of the researcher, and of Te Whāriki: He Whāriki Mātauranga mō ngā Mokopuna o Aotearoa: Early Childhood Curriculum (Te Whāriki) (Ministry of Education [MoE], 2017). An interpretivist paradigm kept the child’s voice and experiences central to the research, whilst allowing the researcher to interpret individual and collective meaning from the children’s experiences and articulations. A qualitative case study methodology provided scope for a number of data collection methods to provide a detailed study of one particular case, which in this research was one early childhood centre. Data gathering methods included audio transcription and observation of puppet play and conversations, research journal, kaiako focus group interview and portfolio analysis. The audio recording and observation of puppet play and conversations with children however, proved to be the most useful methods in exploring children’s perceptions and working theories in this research and has highlighted the importance of story-based play and conversations with children.

Over the course of nine weekly visits, the children and researcher engaged in puppet play and conversations. This yielded 62 audio recordings and observations of children’s puppet play and ten audio recordings of conversations with children. The analysis of portfolios and a kaiako focus group were included to ensure contextual information was gathered that could be used to understand some of the influences on children’s perceptions of kindness. Analysis of data was ongoing and organic. It was useful to begin the analysis of puppet play as it occurred to inform the conversations. Some of these initial insights were noted in the research journal or on the observation schedule. Yin (2012) notes that this is a useful strategy for a case study, whereby the researcher can revisit initial insights in their analysis. Thematic analysis was used to analyse the data using both inductive codes that arose from the data, as well as theoretical codes that emerged from the literature reviewed. This allowed both the latent and semantic data to be recognized (Braun & Clarke, 2006, 2012; Mukherji & Albon, 2015).

Puppet play findings

The puppet play was designed to prompt discussion, inquiry, and meaning making for children involved in this research. This method was designed to make children’s perceptions and working theories of kindness visible. In addition to this, some key findings about puppet play itself emerged. Findings included the development of complexity in children’s narratives over time, as well as the usefulness of puppet play to explore ideas and retell favourite stories. Allowing time and freedom for repetition of favourite or familiar stories will be discussed as well as some practical considerations for this resource in early childhood settings.

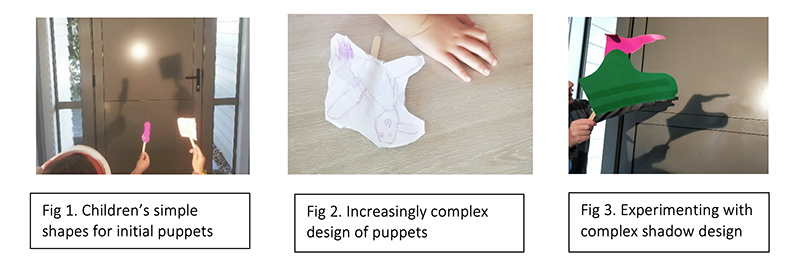

Puppet play created varied literacy and pre-writing skills learning opportunities for the children, not just in storytelling, but also during the creation process. Children often express ideas in non-verbal ways, such as drawings (Pelo, 2007; Pohio, 2006). This initial step was a creative one, in that they were giving their ideas a physical form. This step involved the children learning to use sellotape, scissors and ice block sticks to create shadow puppets. The children experimented with using shapes to create their puppets initially, but with practice and over time, they developed more complexity in their puppet design as seen in Figure 1, 2 and 3 below. It took time for them to create an outline that worked as a shadow puppet. It was anticipated that this creation and refinement process of puppet making would continue throughout the research project so the decision was made in consultation with the kaiako that the overhead projector and puppet play space would be set up adjacent to the puppet making space. This enabled the children to make and test their puppets easily and then return to make refinements as needed. Having an enabling space dedicated to puppet making and puppet play provided children with a sense of predictability and familiarity with the processes involved (Alford, 2015; MoE, 2017) and the children began to anticipate Wednesdays as puppet day.

A significant finding that highlighted the importance of puppet play in the early years was the development of children’s storytelling. Children’s puppet play grew in complexity, length and confidence. When the children first engaged in this play there were no distinct narratives evident in the puppet play, instead the children played around with characters, voices, toilet jokes and pulling faces. This was part of the process of becoming familiar with the medium of puppets, and allowing the children to ‘play around’ with the puppets was an important aspect of children having agency over their play narratives. The children’s comfort in using puppetry as a storytelling and play medium increased over the course of the research. When discussing this with the kaiako at the kaiako focus group interview, the kaiako noted that the children had increased their participation in and conversations about puppet play during the course of the research.

Puppet play requires the children to construct characters, a storyline and then act this out. It took the children some time and practice before they were confident with the medium of puppetry. It was interesting to note that the children were skilled at producing complex pretend play narratives, but did not immediately transfer this storytelling ability to their puppet play. Instead, they chose to revisit and retell familiar stories or build on and expand the provocations given by the researcher. It became apparent in a discussion with one of the kaiako that the children’s prior experience of puppet play was to retell fairy tales. The children were exploring the notion of puppet play in relation to their funds of knowledge of puppets, stories and play (Hedges, 2008). Revisiting fairy tales and familiar stories was an excellent place to start in supporting children’s emerging skills in creating puppet play narratives. In this excerpt, the children are recalling the story of Little Red Riding Hood (Bryan, 2016) and deciding if they would like to use this story as the basis for their next puppet play narrative. Rigel, one of the child participants, is explaining that the intentional deception by the ‘big bad wolf’ could make the others think he is bad. Fleer and Hammer (2013) cite fairy tales as culturally mediating tools used to pass down preferred and culturally acceptable behaviours. This is an interesting consideration, as it shows that storytelling is useful in teaching social norms, as well as oral and visual literacy skills.

Rigel: Yeah um and the mum said don’t speak to strangers.

Researcher: Don’t speak to strangers?

Rigel: Yeah and she did coz the wolf was dressing up as the farmer and so she talked to him.

Researcher: Yeah ok. So why do you think she did that?

Rigel: Coz he was dressed up in someone he wasn’t.

Researcher: Oh ok. So, he was tricking her.

Rigel: Mmmhmmm [nodding]

Researcher: So what do you think about that? Is it ok to trick someone?

Rigel: Nup.

Researcher: Why not?

Rigel: Coz, coz, coz just coz they might think you’re bad.

(Winslow, 2019, p. 105)

The discussion, retelling and reframing of a well-known story can be a useful tool in unpacking more complex notions such as deception, intention and social norms, as in this example. This leads us to consider the value of using conversation to reflect on and further explore children’s perceptions or working theories as well as ways in which kaiako can engage in these conversations. This will be discussed in the ‘implications for kaiako’ section of this article.

Strategies for supporting puppet play

A series of simple strategies to support the children to extend their puppet play narratives such as providing a ‘scene’ on the overhead projector, introducing existing puppets from within the centre into the puppet play space, and allowing the children to incorporate props into the puppet play space, helped the children to develop their own, more complex stories.

To support children to learn about puppet play and puppetry, children were encouraged to explore puppet play in their own way. At times the children took their puppets and incorporated them into their pretend play scenarios with plastic animals, blocks, cars, and Mobilo. The integration of the puppets into centre life was a deviation from the research design; however it showed the children becoming more comfortable with puppets as a medium for storytelling. Early childhood educators acknowledge that trying things out, exploring and playing with ideas are valued ways of learning (MoE, 2017). This is part of the process of becoming puppeteers. The children also brought props into the puppet play area from the doll house to include in their puppet play. Again, children were accessing knowledge gained from prior experiences with storytelling, pretend play and puppet play, a theme noted by Hedges, Cullen and Jordan (2011). The puppet play sessions became more complex over time and despite still wanting to revisit their favourite storylines, the characteristics and voices used for the puppets became more complex and some children, managed to master puppetry to the extent of playing three or four characters at a time.

Initially, when the children were becoming familiar with creating a storyline for their puppet play, the researcher provided a puppet scene on the overhead projector to accompany the provocation, in consultation with the children. This helped the children have a concrete scene to position their characters within. This strategy was only required on two visits before the children were able to remember or create scenes solely by discussing them as part of planning their puppet play narrative. It was a useful interim step in engaging the children in puppet play sessions.

Another useful strategy in supporting children’s puppet play was introducing one or two of the centre’s native bird puppets into the play space. This strategy was designed to assist the children in understanding what a character is and how to use their puppet. The thinking behind this strategy was that the children had existing funds of knowledge from their prior experience with the native bird puppets, and perhaps that could help them to develop their characters and the narrative in their puppet play (Hedges, 2008). This worked well as an example for some children to model their own puppets and puppet play narratives on and as with the other strategies supported children in building complexity and capability in their storytelling.

Puppet play is a fun and effective way to support children’s oral literacy, familiarity with stories and storytelling and exploring children’s perceptions and working theories on a range of topics. It provides a neutral space for children and kaiako to play and make meaning of any number of complex concepts. Using puppet play in a predictable and familiar space, can be a useful teaching tool, providing kaiako with detailed information about children’s thinking, motivation and understandings of the world around them.

Implications for Kaiako

This research showed that kaiako play a significant role in influencing children’s perceptions and working theories, such as kindness. Furthermore, findings suggested that using a narrative play or conversational approach to seek children’s perceptions and working theories could be useful for kaiako in gaining an understanding of children’s perceptions or working theories about their experience of the world around them.

Kaiako as co-puppeteer and co-inquirer

Initially, the researcher’s involvement in the puppet play was a deviation from the intended kaupapa of this research. However, the researcher’s participation in puppet play allowed provocations and challenges to be authentically included which contributed to the researcher’s understanding of children’s perceptions of kindness. The researcher became a co-inquirer and co-creator in the play. Through the relationships that developed during the research, the researcher was able to explore the children’s perceptions and working theories in a relational and responsive manner during puppet play and conversations. Retrospectively, it has brought attention to the importance of the role of the kaiako in meaningful play and conversation with children in order to understand their perceptions and working theories on a topic. Early childhood settings must be mindful to create spaces that encourage meaningful conversations to occur (Moss, 2007). However, this is not without challenge. The role of kaiako as a co-inquirer balances the power inequality inherent in the kaiako-child dyad (Peters & Davis, 2011).

Conversations: An important tool in exploring children’s working theories

Puppet play can be used to explore and understand children’s perceptions and working theories by noticing children’s perceptions or working theories as they emerge in puppet play narratives. Kaiako can then explore these notions further through authentic, and possibly dialogic, conversations with children. Working theories develop in complexity when children are engaged in environments where they can test, inquire and explore ideas (MoE, 2017; Peters & Davis, 2011). From this perspective it seems that puppet play provides a perfect platform for noticing children’s perceptions, emerging notions or snippets of knowledge. However, for kaiako to gain an insight into children’s thinking, motivation or working theories there needs to be further exploration, which allows children to articulate their working theories in more detail.

Working theories are one way of describing the thinking and learning processes that children use to make meaning of their worlds. Working theories can be seen as a type of inquiry, carried out by the child, as they theorise about their world. Working theories are built by sharing, testing and exploring ideas, skills and strategies, which builds understanding incrementally (Hedges, 2011; Hedges & Jones, 2012). Robust working theories the child has constructed over time, contribute to a breadth of knowledge, which allows the child to apply skills learnt in one area to a different area (Claxton & Carr, 2004). Working theories are emphasised by Te Whāriki as valuable learning in the early years, which is outlined as an expected curriculum priority whereby kaiako support children’s developing working theories (MoE, 2017).

The act of engaging in authentic conversation seems a natural approach to gaining an understanding of children’s working theories; however, it is not to be confused with the notion of ‘questioning’ or ‘testing’ children’s knowledge. These conversations about children’s puppet play, in order to be authentic, must be motivated by the curiosity of the kaiako (Hawkes, 2015), whilst being flexible and respectful. In contrast to questioning or testing the child, engaging in conversations gives children the opportunity to think aloud and piece together the perceptions that have emerged from puppet play, into more complex, robust and creative working theories. Kaiako acknowledge the importance of knowing and understanding children’s perceptions and working theories, in order to support this learning (Winslow, 2019). Having a shared experience in the puppet play prior to the conversation, allows the kaiako to analyse children’s perceptions articulated in conversation alongside perceptions expressed in puppet play. Reflective conversations, based on a share experience can illuminate kaiako’s understanding of children’s motivation, intention and beliefs about in a way that observation alone could not.

Dialogic conversations are one way to achieve a shared understanding about a concept (White, 2014). Conversations with children require time and attention (Hawkes, 2015). In order to explore children’s perceptions and working theories, kaiako need to listen deeply to children (Hawkes, 2015). Peters and Davis (2011) found kaiako were more likely to facilitate children's working theories by adding a different material or resource as opposed to listening or talking about children’s working theories. This is in part due to kaiako feeling that they do not have the time to engage in sustained play and conversations with children (Winslow, 2019). This is a concern, given that oral language competency is vitally important to children’s social interactions and their ability to access the curriculum, in turn impacting on future academic and life success (Education Review Office, 2017). Conversations with children, which explore their thinking and lived experiences should be central to an early-years curriculum and consideration needs to be given, at both policy and practice level, to whether kaiako have the time, knowledge and funding to achieve this.

Conclusion

Puppet play and conversations with children have highlighted the complexity and depth of children’s working theories and perceptions in this research. Kaiako are uniquely positioned to support children by engaging with them in puppet play and conversations, which provides a space for children to articulate their perceptions of the world around them, and to develop more complexity in their working theories. Puppet play is a valuable aspect of curriculum when incorporated in a way where the children are free to create stories that draw on their funds of knowledge, allowing them to play around with ideas, language and social situations building capability and confidence in storytelling and oral literacy over time and with practice. Kaiako are encouraged to consider exploring the use of conversational approaches, such as dialogic conversations (White, 2014) to allow children to unpack and explore complex notions that arise in their play. Play is valued as a form of exploration and learning, and that there is a valuable role for kaiako within puppet play.

References

- Alchrona, M. (2012). The puppet’s communicative potential as a mediating tool in preschool education. International Journal of Early Childhood, 44(2), 171-184.

- Alford, C. (2015). Drawing. The universal language of children. New Zealand Journal of Teachers’ Work, 12(1), 45-62.

- Belohlawek, J., Keogh, B., & Naylor, S. (2010). The PUPPETS project hits WA. Teaching Science: The Journal of the Australian Science Teachers Association, 56(1), 36-38.

- Bernier, M., & O’Hare, J. (Eds.). (2005). Puppetry in education and therapy: Unlocking doors to the mind and heart. Bloomington, Indiana: Authorhouse.

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative research in psychology, 3(2), 77-101.

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2012). Thematic analysis. In H. Cooper (Ed.), APA handbook of research methods in psychology. Vol. 2: Research Designs (pp. 57-71). Washington, USA: American Psychological Association.

- Brēdikytē, M. (2000, August/September). Dialogical drama with puppets (DDP) as a method of fostering children’s verbal creativity. Paper presented at the European Conference on Quality in Early Childhood Education (EECERA), London, England. Vilnius: Vilnius Pedagogical University.

- Brown, B. (2005). Combating discrimination: Persona dolls in action. Sterling, VA: Trentham Books.

- Bruner, J. (1986). Actual minds, possible worlds. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

- Bruner, J. (2002). Making stories. Law, literature, life. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

- Bryan, E. (2016). Little red riding hood. London, England: Nosy Crow.

- Claxton, G., & Carr, M. (2004). A framework for teaching learning: The dynamics of disposition. Early Years, 24(1), 87-97.

- Education Review Office (2017). Extending their language – expanding their world: Children’s oral language (birth – 8 years). Wellington, New Zealand: Author.

- Fleer, M., & Hammer, M. (2013) Emotions in imaginative situations: The valued place of fairy tales for supporting emotion regulation. Mind, Culture, and Activity, 20(3), 240-259.

- Hawkes, K. (2015). A pedagogy of listening. Early Childhood Folio, 19(2), 30-34.

- Hedges, H. (2008). “Even when we’re big we’ll still be friends”: Working theories in children’s learning. Early Childhood Folio, 12, 2-6.

- Hedges, H. (2011). Connecting ‘snippets of knowledge’: Teachers’ understandings of the concept of working theories. Early Years, 31(3), 271-284.

- Hedges, H., Cullen, J., & Jordan, B. (2011). Early years curriculum: Funds of knowledge as a conceptual framework for children’s interests. Journal of Curriculum Studies, 43(2), 185-205.

- Hedges, H., & Jones, S. (2012). Children’s working theories: The neglected sibling of Te Whāriki’s learning outcomes. Early Childhood Folio, 16(1), 34-39.

- Hunt, T., & Renfro, N. (1982). Puppetry in early childhood education. Austin, TX: Nancy Renfro Studios.

- Mackey, G., & de Vocht-van Alphen, L. (2016). Teachers explore how to support young children’s agency for social justice. IJEC, 48, 353-367.

- Maybin, J. (2013). Towards a sociocultural understanding of children’s voice. Language and Education, 27(5), 383-397.

- Ministry of Education. (2017). Te Whāriki: He whāriki mātauranga mō ngā mokopuna o Aotearoa: Early childhood curriculum (2nd ed.). Wellington, New Zealand: Author.

- Moss, P. (2007). Bringing politics into the nursery: Early childhood education as a democratic practice. European Early Childhood Education Research Journal, 15(1), 5-20.

- Mukherji, P., & Albon, D. (2015). Research methods in early childhood: An introductory guide. London, UK: SAGE

- Pelo, A. (2007). The language of art. St Paul, MN: Redleaf Press.

- Peters, S., & Davis, K. (2011). Fostering children’s working theories: Pedagogic issues and dilemmas in New Zealand. Early Years, 31(1), 5-17.

- Pohio, L. (2006). Visual art: A valuable medium for promoting peer collaboration in early childhood contexts. Early Education, 40 (Spring/Summer), 7-10.

- White, E. (2014). Bhaktinian dialogic and Vygotskian dialectic: Compatabilities and contradictions in the classroom. Educational Philosophy and Theory, 46(3), 220-236.

- Winslow, R. (2019). Children’s perceptions of kindness. (Unpublished master’s thesis). New Zealand Tertiary College: Auckland, New Zealand.

- Yin, R. (2012). Case study research: Design and methods (4th ed.). Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE.

How to cite this article

Winslow, R. (2020). Exploring children’s perceptions and working theories: Becoming a co-puppeteer, co-inquirer and conversationalist. He Kupu, 6 (3), 51-59.